MA in social Anthropology, University of Kent

Abstract

According to structuralist theory in anthropology, the family unit has an internal order based on the rule ‘no adultery’, but through evolution and transformation, this cultural order can become its opposite. In some cases, this can lead to the violent suppression of individuality, rejection, isolation, harassment, sexual assault and even honour killings. In Iran, sexual abuse by incest is a taboo topic with significant social stigma attached to it. Victims’ fears of punishment and rejection, combined with the lack of registration and reporting, means that there are no reliable statistics or evidence, but some studies show that it is prevalent in Iranian society. This study aims to investigate the causes and factors associated with the sexual abuse of children by family members. It uses semi-structured interviews with 452 people who experienced incest in childhood. The study confirms that child sexual abuse by family members is facilitated by favourable circumstances and makes abused people more vulnerable to their abusers. The study identified several factors that contribute to sexual abuse, including inequality, poverty, patriarchy, ineffective sex education, lack of community support and family dysfunction. These factors lead to subsets of social and individual consequences, such as weakened social relations, early or delayed marriage, interpersonal problems, divorce, dysfunction, negative feelings and a sense of being ‘other’. Efforts to address these underlying factors are necessary to prevent sexual abuse and improve the well-being of victims.

Introduction

NB: Due to the sensitive and taboo nature of this topic in Iran in terms of some elements of the legal system, religious leaders, and government officials and organisations, the names and identities of certain respondents and groups have been changed or removed.

The family has been recognised as a significant social institution throughout history, serving as a safe haven for its members, particularly children. However, despite its role as a sanctuary, family units have frequently become the site of unpleasant occurrences, notably violence against children. Of these occurrences, sexual violence is among the most egregious.

A vast body of evidence links domestic violence to a broad spectrum of sexual violence, which indicates that violence against children is a pervasive phenomenon globally. According to a report published by UNICEF, 257 million to 133 million children bear witness to domestic violence in their families every year (Dalal, 2008). Moreover, a study conducted in 2015 reveals that more than one billion children aged between 1 year and 17 years have experienced physical, emotional and sexual violence (Hillis et al., 2016).

A comprehensive range of behaviours falls under the umbrella of sexual violence against children, ranging from physical and direct sexual contact (such as rape or oral sex) to non-penetrative acts, including masturbation, kissing, touching and rubbing the child’s body. In addition, non-contact activities, such as soliciting children to create or view sexual content or watch sexual acts, encouraging inappropriate sexual behaviour and grooming children for abuse, are also considered forms of violence against children.

Research demonstrates that children are at least twice as likely to be victims of violence from family members than from strangers (Henting, 1978). Moreover, an estimated 13% of individuals who experience rape are assaulted during childhood and within familial contexts (Stoltenborgh et al., 2015).

The issue of sexual harassment has garnered the interest of scholars since the 1980s, given its pervasiveness and far-reaching consequences (Grubb and Turner, 2012). Sexual violence elicits significantly greater attention compared to other forms of violence due to the extensive harm inflicted upon the victim. When such harm is perpetrated by close relatives or within the family unit, the magnitude of the damage is compounded. Often shrouded in silence, such aberrant behaviour is infrequently disclosed. Furthermore, even when such incidents come to light, they can be challenging to believe or prove, as societal norms tend to view the family unit as a haven, free from such harms (Zarei, 2016).

Experiencing traumatic events like rape and sexual abuse during childhood can have lasting negative psychological and social implications on an individual (World Health Organization, 2022). Such consequences include memory impairment, behavioural disorders, such as the propensity for violence against one’s sexual partner (Dube et al., 2005), and depression (Chen et al., 2010). A widely recognised theory posits that individuals who have experienced sexual abuse as children are more likely to perpetrate sexual abuse on their children in the future (Glasser et al., 2001). Moreover, several studies underscore the significant correlation between childhood sexual assault and the likelihood of committing sexual violence and rape in adolescence and adulthood (Babchishin, Karl Hanson & Hermann, 2011).

Sexual abuse can lead to long-lasting harm, including a diminished sense of self-worth, difficulty establishing trust and an impaired ability to form healthy intimate relationships. Survivors of such traumatic events may experience ongoing feelings of guilt, shame and fear, leading to long-term mental health concerns. Additionally, survivors may struggle with physical ailments and chronic conditions, such as pain, insomnia and gastrointestinal problems, further contributing to the complex and multifaceted effects of childhood sexual assault.

Sexual violence, particularly within families, is considered a taboo subject in Iran. Consequently, social stigma, the fear of punishment and the underreporting of incidents make it difficult to assess the prevalence of this phenomenon in the country. Nevertheless, several research studies indicate that sexual violence against children is not uncommon in Iranian society. For example, in research related to prostitution, sexual assault rates were f0und to range between 22% and 25%, while in research related to runaway girls, the range was between 12% and 36%, all of which are significant numbers (Maljou, 2010, 85). Many victims of sexual abuse are reluctant to disclose the abuse due to fear and shame, which leads to underreporting and lower reported statistics than the actual prevalence of the issue (Aspelmeier, Elliott & Smith, 2007). While there are no published statistics on incest in Iran, the head of the Social Injuries Association has recently reported that there have been 5,200 court cases filed in the country regarding sex between siblings or parents and their children. This number excludes other types of incest such as uncle–niece or father-in-law–daughter-in-law relationships, and it is worth noting that many cases of sexual abuse go unreported.

Currently, Iranian society is experiencing a plethora of problems and detrimental phenomena due to its organisational structure and the challenges it faces. One critical issue is the prevalence of violence against children, particularly child sexual abuse. Among the essential features of contemporary Iranian society are social inequality and double poverty, social instability, patriarchal cultural values and ineffective government. These issues have spurred various social changes over the past few decades. For instance, inequality has resulted in the sexual abuse of children by denying many individuals in society opportunities and resources. The growth of social ills like divorce, marginalisation and addiction have exacerbated the likelihood of sexual abuse and inappropriate family relationships. While divorce alone is not a societal problem, it can have severe social consequences, as children of divorced parents and women tend to suffer the most from such arrangements. The formation of alternative family units due to divorce, such as female-headed or single-parent families, or families in which children live with stepparents or other caregivers, can create an environment where children are vulnerable to harm and abuse. Poverty and other social problems compound these issues, making the situation even more dire.

About a quarter of Iranian households are in marginalised areas and neighbourhoods, where they are plagued by absolute poverty. These regions serve as hubs where social problems magnify, yet residents are often unjustly blamed for their plights. These areas lack many urban facilities and services such as proper housing, sewage disposal systems, education institutions and safe public spaces, which makes them susceptible to a plethora of issues including residential instability, concentration of poverty and more. Moreover, due to the lack of regulatory structures in these areas, children are exposed to all manner of abuses. When drug addiction is added to the mix, the situation becomes even more complicated.

That combination of poverty, residing in a marginalised area and drug dependence is one of the primary settings for the emergence of child abuse.

It is, however, important to note that child sexual abuse is not limited to poor families; rather, the context of abuse may vary from one case to another and can manifest in various forms, even among the higher social classes.

Iranian society places women in a subordinate position, which leaves them vulnerable to negative moral labels and mistreatment. The victim of rape is not seen as a normal person or even a victim, but instead is stigmatised as a pervert and a criminal, further oppressing them. This rejection of the victim not only prevents the formation of voluntary support and treatment measures, but also renders government and non-governmental rehabilitation services ineffective for the injured parties. This perspective, which views the sexual victim as immoral and crooked, makes it difficult to establish comprehensive civil actions, and government services cannot be relied upon (Irvanian, 2010).

Meanwhile, the Iranian Government’s disapproval of sex education in schools and other education systems, using ideological justifications, is contrary to the practice in many countries and is recognised in international documents. Sexual education helps raise children’s awareness of sex and teaches them self-care methods and techniques. The lack of systematic access to this education in Iran and the resulting lack of skills and knowledge leave children vulnerable to abuse and violence.

On the one hand, the prevalence of violence against children, particularly sexual violence, is increasing, and, on the other hand, the lack of effective support, the absence of sex education in schools and other organisations and the social stigma associated with this phenomenon create an environment where victims are hesitant to report the abuse they have suffered. Addressing this issue has become increasingly important, especially since the victims of sexual violence are often silenced and left unsupported.

Iranian society’s tendency to stigmatise victims of sexual violence has contributed to the problem. Victims often fear judgment and ostracization, and, as a result, they avoid seeking help. It is critical to provide education about sexual violence, including its consequences and how to prevent it. Creating a safe and inclusive environment for victims to come forward and report incidents is also essential. Such measures must be introduced on both the governmental and non-governmental levels to ensure that children are protected and supported in the face of sexual abuse. Furthermore, it is vital to recognise the importance of sex education and the role it plays in preventing sexual violence. Through these measures, we can begin to address the issue of child sexual abuse and make Iranian society a safer and more equitable place for all.

At the macro level, crafting and implementing policies and legislation are crucial to combat and mitigate this phenomenon. It is essential for any policies and laws to be rooted in research, knowledge and expertise generated in this field, to ensure their efficacy.

Given the prevalence of sexual violence in the family environment and its severe impact on individuals who have experienced it, particularly children, addressing this issue becomes even more crucial. Numerous studies have investigated the various types of violence and the groups most susceptible to it; however, there is still a significant gap in our understanding of the experiences of children, particularly young girls, who have been subjected to sexual violence within their own homes. Therefore, the aim of this study is to examine sexual violence against children in the context of the family environment.

This form of violence encompasses a broad range of actions, including physical contact, rape and exposure to sexual images. A thorough understanding of the underlying causes, lived experiences and outcomes of this phenomenon would enable policymakers and experts in this field to develop appropriate policies and effective interventions to prevent and address this issue in a proactive manner. Such measures should be based on comprehensive research and knowledge that can inform and guide effective policymaking and law enforcement at all levels.

Research such as this serves as a crucial starting point for reflection, recognition and, ultimately, policymaking in response to the issue of sexual harassment. It is imperative for governments to give serious attention to this issue, as sexual abuse not only violates a child’s sanctity, dignity and self-esteem during childhood, but also it affects the child in other periods of life and can perpetuate the cycle. Thus, sound policies must be developed based on scientific findings, the expertise of specialists and the experiences of those who have suffered abuse. Otherwise, sexual harassment may persist and victims and survivors may even face punishment.

Of course, the responsibility for preventing sexual harassment is not solely on governments, as they may lack sufficient capacities in this area. It is necessary to educate and inform society and to provide suitable platforms, particularly for non-governmental organisations, to participate in various ways related to this traumatic issue. Many organisations have first-hand experience dealing with these abuses – with victims, their families and even perpetrators.

For these reasons, this article will be divided into two parts. The first part will investigate the causes and bases of sexual violence against children in the Iranian family structure, utilising a qualitative design and field research. The second part will examine the structural, institutional and individual consequences of sexual violence at the macro and intermediate levels, drawing on expert opinions and analyses. The following question will guide the study:

What are the social, economic and legal foundations on which sexual abuse and violence against children in Iranian families are built?

By answering this question, the author hopes to shed light on the complex nature of sexual violence against children and provide insight into the necessary policies and interventions needed to prevent and address this issue.

2. Research Methodology

Sexual harassment has been a pervasive and persistent problem in human societies throughout history. Despite this, it remains a challenging phenomenon for scientific investigation. The difficulty in accessing a sample from people who are unwilling to cooperate with researchers is a significant obstacle to studying sexual harassment. This issue is further compounded by the fact that sexual harassment is often considered taboo and therefore victims are often reluctant to speak about their experiences. To better understand this phenomenon, it is necessary to employ unconventional methods of investigation.

This problem is particularly acute in traditional societies such as Iran, where sexual harassment is shrouded in secrecy. Despite the challenges, the damage caused by sexual harassment cannot be ignored. Effective policies are needed to combat this phenomenon. These policies must be sensitive to the various forms of sexual harassment and include practical solutions for addressing this issue.

To effectively understand and formulate a theory on sexual harassment, it is crucial to rely on real and empirical evidence and data. Additionally, gaining the trust of both victims and perpetrators and understanding their perceptions and experiences are also essential. Qualitative methods, specifically the Grounded Theory approach, can provide researchers with the necessary techniques and tools to investigate contextual factors, causal conditions, experiences, strategies and consequences of sexual violence against children. Therefore, this research is conducted using Grounded Theory, which can result in the development of a theory or contextual model of the studied phenomenon.

This research aims to investigate individuals who have experienced any form of sexual abuse during their childhood, specifically those who were abused under the age of 18. The study involves a sample of 452 individuals who were selected using a combination of snowball and purposeful-sampling methods. Purposeful sampling allows for the inclusion of individuals with special experiences or knowledge relevant to the research. Data was collected using semi-structured interviews and analysed using the Strauss and Corbin coding process.

3. Research Review

The phenomenon of sexual harassment has been a topic of interest for researchers since the 1980s, due to its prevalence and wide-ranging effects (Grubb & Turner, 2012). Sexual violence is especially concerning as it causes severe harm to the victim, and when it occurs within a family or between people who are related or close to the victim, the damage can be even greater. Unfortunately, this type of abuse often remains undisclosed. Even in cases where it is reported, it can be difficult to believe and prove due to societal views of the family as a safe and loving environment (Zarei, 2016).

Sexual violence against children encompasses a wide range of acts including physical contact, sexual penetration (such as rape or oral sex) and non-penetrative acts such as masturbation, kissing, rubbing and touching of the child’s body. Additionally, it includes non-contact activities like encouraging children to engage in inappropriate sexual behaviour, grooming them for abuse, and producing or viewing sexual images. Research has revealed that children are twice as likely to be victimised by family members or acquaintances than by strangers (Hunting, 1978). Approximately 13% of individuals who have been raped experienced the abuse during childhood, within a familial environment (Stoltenburg et al., 2015).

Enduring traumatic experiences such as rape and sexual abuse during childhood has long-term psychological and social consequences, including memory problems, behavioural disorders such as domestic violence (Dube et al., 2005), and depression (Chen et al., 2010). A prominent theory of child sexual abuse posits that those who have been victimised as children are more likely to become perpetrators of sexual abuse in the future (Glasser et al., 2001). Additionally, several studies show that experiencing rape during childhood is a significant factor in committing sexual violence and rape in adolescence and adulthood (Babchishin, Karl Hanson & Hermann, 2011).

4. Causes of Sexual Abuse of Children in the Family

The sexual abuse of children is caused by a complex interplay of economic, social and legal factors. Not only do these factors contribute to the occurrence of child sexual abuse, but also they contribute to the mechanisms that perpetuate and intensify the problem and its consequences. Violence is often a result of deprivation, which can then lead to the sexual abuse of children. Cultural and social structures can further exacerbate the issue by causing the victim to fear rejection and criminalisation, which may result in denial of the abuse and a failure to report the abuser.

Without appropriate policies and social, economic and legal support for victims, the cycle of sexual abuse of children will continue to escalate. This dialectical relationship between social institutions at the macro, medium and micro levels of society creates and perpetuates crises.

In the following sections, we will discuss the main causes and factors underlying this issue.

4.1 Economic Causes

Studies in this field reveal that the economic factor is crucial in the genesis and perpetuation of the sexual abuse of children. Economic factors such as poverty, unemployment, type of occupation and housing contribute to the prevalence of violence and sexual harassment. The economic dimension is associated with fulfilling the basic needs of the family, and any disruption in this regard, such as inadequate income, can trigger problems.

Poverty often leads to child neglect, when families struggle to meet the basic needs of their children and provide adequate care for them. Consequently, the children’s development and social skills are hindered. As they grow up, they may lack proper communication skills and find it difficult to form healthy relationships with the opposite sex. Due to the financial constraints, they may not have access to legitimate channels for satisfying their needs, leading them to resort to violent means. Moreover, poverty may also affect parents’ awareness of appropriate parenting skills.

Additionally, poverty can result in people residing in disorganised neighbourhoods and areas that lack proper infrastructure. These areas are often characterised by factors such as high population density, residential instability, inadequate security measures and breakdowns in the social capacity of residents to manage their environments. As a result, the likelihood of various crimes, including violence and rape, increases. In societies like Iran, where poverty is often associated with other negative phenomena such as inequality, inefficiency and addiction, there are specific areas with structural vulnerabilities to sexual harassment.

The type of housing can also have an impact on child sexual abuse in cases of poverty. Poor households often live in small dwellings where the lower-floor area of the house causes children to hear their parents engaging in sexual activities or all family members may have to sleep together in the same room at night. This increases the risk of sexual assault and rape.

The economic aspect of deprivation has an impact on both individual and social self-awareness. In recent decades, the monetisation of the educational system has been accelerating in Iranian society. As economic problems and disruptions intensify, more groups in society are being excluded from education, as well as cultural and artistic opportunities. One of the consequences of this is a lack of self-care skills and an inability to properly care for children and teenagers within the family institution.

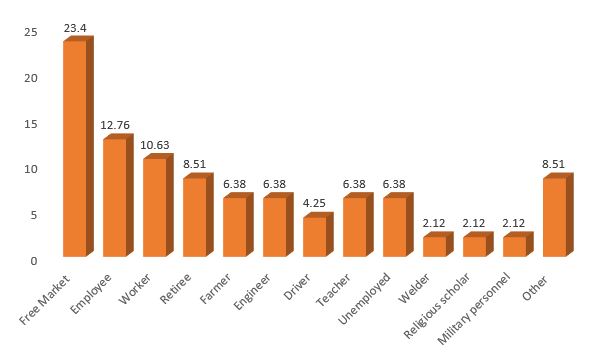

From the findings of this research, it can be inferred that the low socioeconomic status of parents, indicated by their level of education and housing situation, is a significant factor in child sexual abuse. This highlights the correlation between economic deprivation and other forms of deprivation, when economic hardship impacts the level of social awareness and the quality of social interactions.

Diagram 1: Distribution of respondents by educational level of parents

Diagram 2: Distribution of respondents according job of father

Diagram 3: Percentage distribution of respondents according to job of mother

Poverty can also lead to a situation where a divorced mother is compelled to enter into a marriage she does not desire, solely for the sake of having a provider and meeting her expenses. Such households are at high risk of child sexual abuse. Families affected by deprivation, both economic and non-economic, may experience negative emotions such as fear and guilt; hold beliefs related to honour, dignity and social approval; and suppress their needs due to a reward-and-punishment system. In extreme cases, they may even force the abused child to marry to restore their reputation.

4.2. Socio-Cultural Causes

The cultural context is a significant factor in creating an environment conducive to sexual violence. A patriarchal subculture endows men with the audacity and authority to perpetrate sexual violence within their familial relationships, while notions of respect, honour and shame inhibit them from addressing such situations. In Iran, where socialisation and education institutions contribute to the culture of denial and secrecy, discussions about sexuality are prohibited and deemed taboo. This is reinforced through religious discourse.

The provision of sexual education requires collaboration between various institutions. These include the family, schools, media, religious institutions, governments, and policy-making bodies that allocate budgets for such education. Effective and comprehensive sexual-education programmes require coordination among these institutions. In Iranian society, however, institutional interaction faces obstacles due to overlapping roles, conflicts of interest and negative attitudes towards one another. Consequently, sexual education has been neglected. The presence of opposing views and dualistic attitudes has also contributed to the failure of sexual education in Iranian society.

Social attitudes are a major impediment to sex education in Iranian society, stemming from the socialisation process. Cultural values of shame, guilt, dishonour and fear are deeply ingrained in Iranian culture and hinder discussions about sexuality, which is considered taboo and is therefore stigmatised. Consequently, victims of sexual harassment are prone to keeping it a secret, allowing perpetrators to continue their abuse.

Diagram 4: Distribution of respondents according to reasons for secrecy

The initial step in planning and implementing policies for sex education is acknowledging the existence of the problem. The lack of trust in sex education by parents, coaches and teachers in Iran’s education environment, along with the failure to teach children self-care measures, has led to unpleasant incidents.

At a structural level, one of the primary reasons for the absence of sexual education for children is the conservative and ideological nature of policy-making institutions. In Iranian society, religion holds considerable influence over policy-making institutions, with many officials and policymakers being clerics. The Islamic perspective on sexuality is negative, and this religious discourse, by dominating the legal, social and cultural structures, has legitimised the suppression of sexuality and the lack of discussion and education about it. As a result, systematic sex education is non-existent in society, and responsible institutions often impede the efforts of individuals who feel accountable in this field.

In addition to education, supporting victims is crucial. When a child experiences sexual abuse, it is important for support institutions to provide assistance in various ways. However, there are significant challenges to providing effective support in crisis centres. Due to the extensive nature of the problem and the numerous systematic limitations and obstacles faced by intervening and supporting institutions, the current interventions do not function well.

The gender of an individual is significant in determining the nature and extent of sexual harassment in a culture that perpetuates sexism. Research indicates that women are more likely to experience sexual harassment from their intimate partners than men. This disparity highlights the impact of traditional biases, attitudes and gender stereotypes in education and socialisation, which can perpetuate discrimination and unequal treatment.

4.3. Legal Causes

The insufficiencies of the criminal justice system along with the absence of policies, programmes and executive assurances of protection measures for victims of sexual violence are among the legal problems in Iran. Prior to the enactment of the Law on the Protection of Children and Adolescents in 2020, there was no particular legislation safeguarding children who had been sexually abused, punishing perpetrators or ensuring protection to prevent them from reoffending. The Islamic Penal Code was the foundation for addressing such incidents, but the passage of this law addressed some of the gaps in this area.

The legal system’s failure to punish sexual abusers is legitimised by a discourse that stems from the patriarchal culture dominating society and is based on gender discrimination. Additionally, economic factors often result in the punishment for sexual harassment being reduced to a mere fine, reinforcing this cultural discourse. This failure to adequately punish sexual abusers often leads to repeated occurrences of sexual abuse, including instances of adultery and incest.

After reviewing the opinions of the participants in the study, three main themes were identified: insufficient legal protections, the lack of enforcement of existing laws and the influence of patriarchy in legal systems. Some participants argue that there are no specific laws protecting sexually abused children or addressing sexual abuse in general.[2] In practice, there are inadequate procedures and mechanisms in place to enforce existing laws and ensure their effectiveness.

Iranian law has a fundamental problem regarding the age of childhood. Various ages are determined in Iranian law, such as the age of marriage, the age of commencing work, the age of puberty and the age of criminal responsibility. Additionally, legislators use three terms, namely ‘child’, ‘minor’ and ‘adolescent’, to refer to the period of childhood, indicating a lack of consensus in this regard. The lack of a clear distinction between these periods has led to new difficulties in the matter of sexual harassment.

The Islamic Penal Code defines a ‘child’ as a person under the age of 15. Article 221 states that adultery is sexual intercourse between an unmarried man and woman, and if one or both parties are minors, the minor(s) will not be punished, but will receive protective and educational measures.

Article 224 lists death as a punishment for adultery in cases such as adultery with relatives.

Article 91 states that adultery must be proven by the testimony of four righteous men or three righteous men and two righteous women, and, if proven, the punishment may be either flogging or stoning. However, this law has several problems; for example, it sets the age of childhood at 15 years, whereas many international conventions of which Iran is a member define childhood as ending at 18 years of age. Additionally, imposing the death penalty is not only ineffective in preventing sexual crimes, but also violates human dignity, and restorative justice should be implemented instead. Finally, historical evidence reveals that sometimes child victims of sexual abuse are wrongly accused of adultery.

The Law on the Protection of Children and Adolescents does not address the issue of adultery explicitly, but covers topics such as sexual abuse, prostitution, obscenity, imminent danger and pornography, wherein any child abuse in these cases will result in intervention. However, the law’s definition of ‘childhood’ is vague, and it includes the age of religious maturity, which is nine for girls and 15 for boys, reflecting gender discrimination. The definition of ‘teenager’ is ‘any person under 18 who has reached legal maturity’. The law’s foundation in Sharia law raises fundamental issues, and there is ambiguity regarding the precise definition of ‘childhood’ in various areas. Article 2 states that ‘this law applies to all persons under 18 years of age’, but the age of childhood is not precisely defined, leading to confusion.

4.4. Family Causes

Factors such as familial disorder, authoritarianism and isolation, or weakness in terms of marital and familial bonds can accelerate sexual violence or child sexual abuse at the family level. Disorganised and dysfunctional families can take various forms.

Based on structure, the main types of disordered families identified in this study include patriarchal and religious families, divorced families, families with one guardian absent due to death or separation, families with guardians in prison, large and extended families, families lacking a suitable guardian, families with stepparents and step-siblings, families with a deceased mother and a stepfather, families with a polygamous father, and step-siblings with age differences.[3]

While families are often safe havens, they can also be dangerous for children due to violence and sexual abuse. Sexual abuse can occur in any type of family, including religious families. In fact, the suppression of feelings and needs often imposed by religious texts and restrictions can lead to a degree of sexual stimulation and even sexual abuse. Religious families may institutionalise feelings of guilt and shame, which can lead victims of sexual abuse to feel these emotions and blame themselves. Gender roles are often strictly divided in religious families, with the father or man being the owner of everything, including family members and assets. Children and other family members may not have the right to protest against him, and any dissent may result in punishment. These factors, along with others such as disordered and dysfunctional family structures, can contribute to the occurrence of sexual violence and child sexual abuse within families.

Although a family may be free from certain harms such as addiction, divorce and bad parenting, it may not necessarily be balanced. Some families are structured in ways that are either too strict and involved or too permissive and distant, which can lead to a suppression or imbalance of people’s feelings and needs. Such imbalances may lead to sexual harassment and adultery.

Extended families with large numbers of members can also contribute to the risk of abuse. In some cases, impoverished parents may have more children in anticipation of having support in their old age. However, these households often lack the resources to meet the basic needs of their children, and the increased number of dependents further strains the family’s resources. Additionally, without a specific plan or strategy for raising their children, many of these families may leave their children neglected and vulnerable to abuse. On the other hand, having a large number of family members can also act as a protective factor and serve as a support system for the children.

It is crucial to consider the family dynamic between abusers and child victims in cases of sexual abuse. Abusers within the family can perpetrate different forms of sexual harassment – one category being incestuous. Incest involves a deep connection between the child and the abuser, who may be a family member such as a father, mother, brother or sister. Given that these individuals are sources of support and security for children, experiencing abuse from them can be particularly traumatic and put children’s safety at risk. It also means that children have nowhere to turn for protection. In some cases, when a father or stepfather abuses a child and the mother is aware of the abuse, she may not provide assistance for fear of losing her husband and being left without a source of support. This can lead to continued abuse.

The parent-child relationship is built on attachment and a sense of heroism, with children relying on their parents for guidance. Sexual abuse can shatter this perception, causing confusion and conflicting emotions in children, resulting in serious psychological harm such as feelings of fear, anger and guilt. This can lead to dependent individuals who struggle to develop personal maturity and independence.

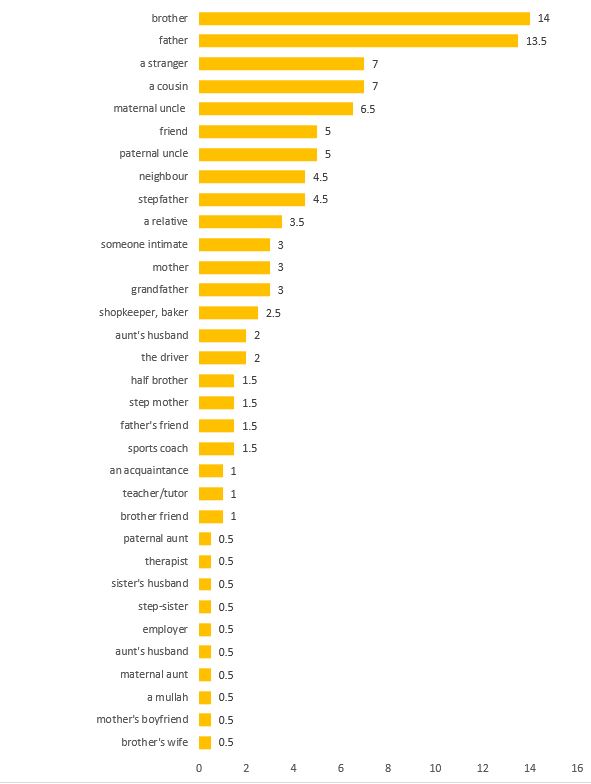

Diagram 5: Distribution of respondents

according to number and proportion of harassers

The second category of abusers consists of ‘secondary’ family members, such as stepfathers, stepmothers, step-siblings, uncles, grandfathers, grandmothers and likewise. Unlike primary family members, these individuals have less responsibility towards the child and their levels of interaction with the child may not be extensive. However, this group may also pose a risk of abuse to children due to their relationships with them. Additionally, because these individuals may not consider children as first-class family members and may not be held responsible for them, they may be more likely to harm them without concern for the consequences.

The third group of abusers consists of non-immediate family members, such as the spouses of aunts and uncles or cousins. This group poses a high risk for child abuse due to their close relationships and easy access to children. Sometimes, parents may even entrust their children to these family members for care, which can further increase the risk of abuse.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, there are strangers who the child has no prior relationship or connection with. In this type of situation, harassment often takes the form of physical attacks and is highly dependent on the child’s environment. For instance, if the abuser notices that the child is alone and unattended in a certain environment, they may take advantage of the situation and attack the child.

Diagram 6: The range of harassers

Family practices, specifically how children are raised, play a significant role in instances of sexual abuse. Research has identified several key components of ineffective parenting practices that contribute to such abuse. These include a lack of affection and love in the family environment, physical and emotional abuse of children, neglect of children’s needs, absence of verbal restraint among family members, inadequate supervision or guardianship, parental addiction and mental illness, harsh family rules, uncontrolled living environments for children, entrusting children to inadequate caregivers, lack of effective protection, failure to report incidents of abuse, imposing economic restrictions on children, blaming and criticising the child, living with a domineering grandmother, incorrect beliefs on the mother’s part, inadequate parenting skills and a lack of education from the family.

Parental substance addiction can become a breeding ground for child abuse in various ways. If parents, or even one of them, are addicted to substances, they become less capable of giving their children the attention and love they need, as their focus and energy is consumed by the preparation and consumption of drugs. Addiction can turn a family into a hub of conflict, violence and aggression by altering or even eliminating roles in the family, disrupting the division of labour system and damaging the emotional equilibrium of the family.

Children of single-parent or single-guardian families are also at a higher risk of sexual abuse by their guardian’s intimate partners. Such families are present in modern societies across the globe, including in Iranian society, where a variety of conditions and circumstances can lead to this family structure. However, social institutions that support and assist these families may operate more effectively and with greater confidence in developed societies with stronger social welfare and policies, compared to in societies like Iran, which face economic challenges and a dominant political system that impacts the style of economy.

4.5. Individual Causes

The acceleration of sexual harassment can be attributed to certain characteristics of both victims and perpetrators, but determining which factors play more significant roles in the occurrence of child sexual abuse is not a straightforward matter and requires further discussion.

4.5.1. The Individual Characteristics of Victims

Certain personal characteristics can increase the likelihood of an individual becoming a victim of sexual harassment. This study has identified several traits that make individuals more vulnerable to abuse and its continuation, including physical and mental disabilities, low IQ, physical differences, beauty, passivity, non-conformity to local cultural norms, immigrant status, addiction, hyperactivity and bullying. However, the existence of these characteristics does not mean that other children are immune to abuse; rather, it highlights that this group may be at a higher risk of being abused. Children with dysfunctional personality traits are particularly susceptible to abuse, particularly from those who are close to them, making it difficult for them to respond effectively to prevent such abuse.

Two notable characteristics among the abovementioned traits are the inability to defend oneself and the inability to report the abuse. Additionally, this group of children is different from other children, which makes them more vulnerable. For example, children who are unable to defend themselves due to physical or mental disabilities are more likely to be targeted by abusers. This distinction in a child’s characteristics has been identified in various discourses as a contributing factor in sexual abuse by individuals close to them.

In addition, the research narratives highlight the vulnerability of children who have limited speaking and communication abilities. This lack of communication skills can make them easy targets for sexual abusers. Furthermore, children with mental disabilities, hearing or speech impairments, physical disabilities and other similar conditions are often targeted by abusers. In some cases, parents and other family members may even abuse these children, considering them to be the cause of the family’s problems and knowing that they cannot defend themselves. Due to these characteristics, these children may not be able to report the abuse, which makes them more vulnerable to ongoing exploitation by the abuser. How each country addresses this issue varies depends on its level of development and its social and economic status.

However, it is important to note that even children without any special characteristics or disabilities can still be subjected to various forms of sexual abuse. In fact, such abuse can even cause certain characteristics to develop, such as isolation and withdrawal. Weakness in skills, such as the ability to assert boundaries and think critically, as well as personality traits like low self-esteem, anti-social behaviour and isolation, along with negative emotions such as anger, fear, guilt and shame, can create favourable conditions for sexual harassment. These characteristics, combined with abusive behaviours, can provoke and enable the harassment to continue.

4.5.2. Individual Characteristics of Harassers

The personal characteristics of perpetrators of sexual harassment are also important to consider. These aggressive traits include low tolerance for failure, difficulty controlling anger, lack of empathy towards family members, verbal and physical aggression, drug and alcohol abuse, anxiety during sexual activity with adults, paedophilia, a history of childhood sexual abuse, suspicion towards family members, borderline antisocial tendencies, neuroticism, sexual impulsivity, loneliness, stereotyping of sexual roles, low self-esteem, emotional instability and self-regulation problems. Health problems may also contribute to these behaviours. In interviews, victims reported that feelings of shame, blame, guilt and fear and a sense of ownership were commonly expressed by their abusers.

Irrespective of the moral perspective, sexual harassment can be viewed as a form of communication with the outside world. For individuals with antisocial personalities, their social lives may not have provided them with opportunities to satisfy their needs through healthy and balanced social relationships. It is important to examine the domineering and bullying tendencies of abusers in situational contexts, as an abuser is in a position of power over the victim at that moment and may have been in the opposite role in a different situation.

5. Recommendations

The following suggestions and solutions for addressing child abuse are derived from three primary sources: (a) the experiences of individuals who have been abused; (b) recommendations from experts and professionals in the field who were interviewed; and (c) existing literature on child abuse at the macro, medium and micro levels.

At the macro (structural) level:

- Implement education and welfare policies that address multi-dimensional deprivations in Iranian families through government and non-governmental organisations and support organisations.

- Develop regional and neighbourhood policies to alleviate poverty and monitor defenceless areas.

- Strengthen non-governmental organisations.

- Ensure public safety in community spaces.

- Improve coordination between educational, legal, medical and social institutions and develop educational programmes to help sexually abused children, while maintaining confidentiality and ensuring their safety.

At the middle (institutional) level:

- Develop content to teach children about sex.

- Strengthen the educational function of schools.

- Train coaches, teachers and school officials on how to deal with children who are victims of sexual abuse.

- Pressure governments and legislators to amend laws and reduce the gaps between jurisprudential laws, the Convention on the Rights of the Child, and the law’s effective implementation.

- Eliminate and reduce gender perspectives in curriculum and media.

- Create intervention-and-treatment centres with an emphasis on high-risk areas.

- Develop plans to prevent further harassment by aggressors.

- Teach children social and individual awareness to actively stand up to abuse in the home and community environment.

At the micro (family) level:

- Increase knowledge and skills of families and children through age-appropriate education and information.

- Critically review socialisation and parenting styles.

- Raise awareness about the harms of hiding sexual harassment and delegitimise the construction of shame, modesty and honour.

- Teach children to resist sexual requests and strengthen their abilities to say no.

6. Conclusion

Sexuality, as a construct, is a socially influenced phenomenon, shaped by cultural norms and social relations. Effective education can manage it. However, in Iranian society, the dominant moral discourse makes taboo unconventional sexual relationships, making it challenging to investigate sexual harassment in all its dimensions. Moral standards are subjectively prescribed and the dominant discourse treats sexual harassment as dishonourable. Victims are blamed, and the domination of the abuser is legitimised through the rejection, blame and punishment of the victim.

This study shows that structural and functional problems and crises in socialisation and support institutions in Iranian society have led to the sexual abuse of children in the family, which, instead of being addressed, prevented and moderated, provides a platform for other social harms, such as children running away from home and being forced into marriages.

In Iran’s religious and ideological society, the guardian’s view dominates all areas of the social system and the individual sphere, and the norms that legitimise them provide a cover based on protection and not being contaminated by sin. These norms are institutionalised in such a way that they prevent or ‘justify’ abuse, in some cases. The sexually abused person is often left unsupported, and the lack of support can fuel the problems and social harms of the same society, continuing a vicious cycle. The most important causes of child sexual abuse are poverty and deprivation, disordered families, the ineffectiveness of institutions in providing sexual education and support, the lack of clear law, and conflicts and contradictions between existing laws.

If appropriate measures are not taken to prevent and moderate child sexual abuse, it will create and intensify other issues and social harms and hinder society’s development.

The logical conclusion from the main findings of the study is that the causes of child sexual abuse in Iran are multifaceted and complex. One of the primary factors is poverty and deprivation, which can lead to a range of issues including lack of education, poor living conditions and reduced access to healthcare. Disordered families and weak family structures also contribute significantly to this problem. Children from such families are often exposed to physical, emotional and sexual abuse, which can have long-term impacts on their physical and mental health.

In addition, the ineffectiveness of institutions in providing sexual education and support is a significant factor that contributes to child sexual abuse. The lack of effective educational programmes and support mechanisms means that children are not equipped to identify and report sexual abuse, nor do they have the support structures in place to help them cope with such experiences.

Moreover, the absence of clear and concise laws on the prevention and treatment of child sexual abuse, as well as the conflicts and contradictions between existing laws, further exacerbate the problem.

Therefore, addressing the issue of child sexual abuse requires a comprehensive and multi-faceted approach that targets all these underlying causes. This would involve implementing effective educational programmes that equip children with the knowledge and skills necessary to protect themselves against sexual abuse, strengthening family structures and support mechanisms, improving living conditions for families living in poverty, and enacting clear and effective laws that protect children and hold perpetrators accountable. By addressing these factors, it is possible to prevent and mitigate the negative impacts of child sexual abuse in Iranian society.

Works Cited

Ahmady, K., et al. (2016). Echo of Silence: a comprehensive research on early marriage of children in Iran. Shirazeh Publishing.

Ahmady, K., et al. (2023). Taboo and secrecy: a study on child sexual abuse with an emphasis on adultery in Iran. Avaye Buf.

Aspelmeier, J. E., Elliott, A. N., and Smith, C. H. (2007). Childhood sexual abuse, attachment, and trauma symptoms in college females: The moderating role of attachment. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31(5), 549–566.

Babchishin, K. M., Karl Hanson, R., and Hermann, C. A. (2011). The characteristics of online sex offenders: A meta-analysis. Sexual Abuse, 23(1), 92–123.

Chen, L. P., Murad, M. H., Paras, M. L., Colbenson, K. M., Sattler, A. L., Goranson, E. N., and Zirakzadeh, A. (2010). Sexual abuse and lifetime diagnosis of psychiatric disorders: systematic review and meta-analysis. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 85(7), 618–629). Elsevier.

Dalal, K. (2008). Causes and Consequences of Violence Against Child Labour and Women in Developing Countries, 1–41. Karolinska Institutet.

Dube, S. R, Anda, R. F., Whitfield, C. L., Brown, D. W., Felitti, V. J., Dong, M., and Giles, W. H. (2005). Long-term consequences of childhood sexual abuse by gender of victim. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 28(5), 430–438.

Edleson, J.L. (1999). Children’s Witnessing of Adult Domestic Violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 14(8), 839–870.

Glasser, M., Kolvin, I., Campbell, D., Glasser, A., Leitch, I., and Farrelly, S. (2001). Cycle of child sexual abuse: Links between being a victim and becoming a perpetrator. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 179(6), 482–494.

Grubb, A., & Turner, E. (2012). Attribution of blame in rape cases: A review of the impact of rape myth acceptance, gender role conformity and substance use on victim blaming. Aggression and violent behaviour, 17(5), 443–452.

Henting, A. (1978). The Criminal and His Victim. California Commission on the Statuses of Women Domestic Violence Fact Sheet 1948.

Hillis, S., Mercy, J., Amobi, A. and Kress, H. (2016). Global Prevalence of Past-year Violence Against Children: A Systematic Review and Minimum Estimates. Pediatrics, 137(3), e20154079. DOI 10.1542/peds.2015-4079.

Irvanian, A. (2010). The re-traumatization of sexual victims in the context of society’s responses and the criminal justice system. Law Research, 12(29), 1–24.

Maljou, M. (2010). Intimate rape: contexts, strategies of the aggressor and reactions of the victim. Social Welfare, 9(34), 113–83.

Margolin, G. and Gordis, E. B. (2004). Children’s exposure to violence in the family and community. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13(4), 152–155.

Stoltenborgh, M., Bakermans‐Kranenburg, M. J., Alink, L. R., and van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2015). The prevalence of child maltreatment across the globe: Review of a series of meta‐analyses. Child Abuse Review, 24(1), 37-50.

Turner, D., and Rettenberger, M. (2020). Neuropsychological functioning in child sexual abusers: A systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behaviour, 54, 101405.

Vameghi, M., Faizzadeh, A., Mirabzadeh, A., and Faizzadeh, G. (2007). Exposure to domestic violence in high school students of Tehran. Social Welfare Scientific Research Quarterly, 6(24), 305–325.

World Health Organization (2022)Violence against children. (2022, November 29). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-children

Zarei, M. H. (2016). A comparative study of privacy protection in cyber space with an emphasis on the new regulations of the European Union. Presented at the International Conference on Legal Aspects of Information and Communication Technology.

- Researcher and anthropologist: https://kameelahmady.com and [email protected]. ↑

- Since the Law on the Protection of Children and Adolescents has been passed recently, it is natural that the interviewees who were interviewed in 2019 did not know about the existence of such a law. ↑

- Of course, all these types of households are not necessarily disordered, but they are structurally different. It should be noted that this type of family is not necessarily a breeding ground for abuse, but the possibility of abuse is higher in these families. This form of family is not limited to a specific socio-economic class and exists in all classes, because human bonding and its meaningful and effective nature cannot be reduced to a single factor. Dysfunctional families and families that lack parenting skills exist in all classes. ↑

Farsi (فارسی)

Farsi (فارسی) Kurdish (کوردی)

Kurdish (کوردی)