Temporary Marriage

An Approved Way of Submission

Abstract

Temporary marriage is a multi-dimensional topic. It allows Muslim men and women to be considered as husband and wife for a limited and temporary fixed time (Johnson, 2013) after specifying a Dowar, the bride price paid by the groom or his family.

(Manzar, 2008). In Arabic dictionaries “Mut’ah “is defined as ‘enjoyment, pleasure, delight’. The present study is a step towards deeper understanding of the social matter.

There are pros and cons associated with this social ritual, however the unseen burden carries enough weight when it comes to women. This article aims at clarifying various aspects of temporary marriage and indicating the pertaining consequences on women which have remained hidden from the public eye and even the researchers so far.

This study reveal the fact that while temporary marriage is playing a role to legalize illicit relationships, on the other hand, subjugate women in the name of protection. The study has been conducted in the framework of interpretivism and the approach of qualitative research. Using field theory approach, the research was performed in three metropolitans of Tehran, Isfahan, and Mashhad.

Due to the cultural and religious vulnerability of the research topic and difficulty of reaching the samples, probability sampling has been used. Theoretical saturation and data saturation was achieved after having 100 interviews.

More interviews were conducted however, in order to make the results more reliable. The researchers agreed on theoretical saturation and comprehensiveness of the research after interviewing 216 people. However, the experts for qualitative method contributed in supervision and providing guidance throughout the study.

Of the 216 interviewees, 35% were men and 65% were women. Data of the present study have been collected through free and in-depth interview technique. The interviews were conducted first and then they were analysed and interpreted through theoretical coding (open, axial and selective). In order to collect data, and for the purpose of reaching important concepts and categories of participants, informal interview method was applied.

At the second stage, the concepts and categories achieved in the process of interview were pursued in line with sampling. When the general themes of interviews were formed through concepts and categories, interview questions were standardized by semi-structured interview method.

The process was continued until theoretical saturation was achieved. Afterwards, major categories, sub-categories and concepts were achieved through implementing open coding and simultaneously with data collection. Through axial coding, sub-categories became related to each other and also to major categories. Types of categories were also identified in terms of being causal, procedural and consequential.

Keywords: Temporary Marriages, Sigeh, Women, Iran, Culture, Gender, Equality, Religion

Temporary Marriage (Sigheh or Mut’ah)

From Islam’s point of view marriage has several benefits and the philosophy of marriage necessity is formed based on its advantages (Tiliouine, Habib, Robert A. Cummins, and Melanie Davern., 2009).

Preservation of human generation, mental and physical tranquility and equilibrium, moral and social health of society, meeting human natural and instinctive needs, and satisfying the need for loving and being loved, etc., are among the advantages of marriage.

The Islamic jurists (Faqih) counted marriage as an emphasized recommendation (Mustahab Moakad) according to the hadiths and anecdotes they have narrated on marriage importance; they consider marriage compulsory (wajib) for those who may commit a sin due to being single.

Based on Islam, man and woman become halal (permissible) to each other through marriage and marriage contract is signed in two forms of permanent and temporary (Rizvi, 2014).

In permanent marriage, no duration is specified and the woman undergoing this kind of marriage is called Daemeh (permanent); in temporary marriage, duration of matrimony is specified and the woman is married for one hour, one day, one month, one year or longer.

However, marriage duration should not exceed the lifespan of wife or husband; otherwise the contract will be annulled. The woman practicing this kind of marriage is called “Mut’ah” or “Sigheh” Of course, there are disputes over maximum duration of temporary marriage.

Some people believe that marriage duration should not exceed lifespan of man or woman and the contract will be annulled otherwise. But majority of the religious scientists believe that the parties can marry for a long period of time, for instance for 50 years or even longer; but the exact period of time should be mentioned in Sigheh contract.

Therefore, temporary marriage or discontinuous marriage which is discussed in this article is a type of marriage approved by Shia jurists; on the contrary, this type of marriage is illegitimate in Sunni Islam (Murata, 2014).

Prevalence of Temporary Marriage in Iran and Contributing Factors

The marriage pattern has changed in Iranian transitory society, which has evolved dramatically towards modernity. (Najmabadi, 2013) This has been principally seen in the significant decreased falling marriage rate whilst divorce has progressively increased (Abbasi-Shavazi, Mohammad Jalal, and Peter McDonald, 2012).

Despite the growth in the number of youth of marriage age, reaching almost 11.5 million in 1396 (March 2017-18), the marriage rate has decreased by 3.5% compared to the previous year and by 8% compared to 1389 (March 2010-11).

Figures show that marriage rate has not increased in alignment with the country’s population. Experts believe that continuance of the decline in the marriage rate, in turn is having a negative effect on the country’s demographics.

This decline is the source of many concerns and in turn is having a negative effect on the country’s demographics and harms to society as the shift in the demographics to a shrinking and ageing population. This is when temporary marriages comes into play. The proliferation of “temporary marriages” shows how Iranians are using Islamic Sharia Law to establish parallel forms of marriage that are otherwise illegal.

Preventing sin and corruption, satisfying the biological sexual instinct, getting to know each other for permanent marriage, gaining mental and spiritual tranquillity, and lack of required facilities for permanent marriage are the often cites reasons for temporary marriages.

(Haeri, 2014). In recent years, based on these reasons, government and policymakers have promoted temporary marriage as a solution, through media campaigns, issuing license of establishing registry offices for temporary marriage, and launching different internet sites.

Before 1335 (1956-57), temporary marriages were officially sanctioned with marriage registry offices having the authorisation to issue temporary marriage certificates.

However, between 1962 and 1978, the Iranian women’s movement gained tremendous victories: women won the right to vote in 1963 as part of Mohammad Reza Shah’s White Revolution, and were allowed to stand for public office.

In 1975 the Family Protection Law provided new rights for women, including expanded divorce and custody rights and reduced polygamy.

Under Her Imperial Majesty Empress Farah Pahlavi of Iran—as she was officially known until 1979, when her husband, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, was overthrown and replaced by the Islamic Republic of Ayatollah Khomeini the government supported advancements by women, opposed child marriage and polygamy.

Temporary marriages were not permissible (Pahlavi, 1978). Given that in many cases temporary marriage was committed by married men, the ban on polygamy undermined temporary marriage in official centres.

After the Islamic Revolution of Iran, Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani Akbar, one of the leaders of the Islamic Republic of Iran fourth President of Iran from 1989 until 1997, tried to defend temporary marriage in different circumstances (Dabashi, 2017). He was the first person to discuss it openly during his presidential mandate.

In 1990, he spoke of temporary marriages for the first time at Friday congregation prayers as a solution for preventing moral corruptions in society. In his sermon he called sexual desire a God-given trait.

Don’t be ”promiscuous like the Westerners,” he advocated, but use the God-given solution of temporary marriage. That sermon brought thousands of protesters to Parliament, in part because a married man can have as many temporary wives as he wants, up to four permanent ones, and can terminate the contract anytime he wants. Whereas women cannot. (Sciolin 2000).

He stated that: “A government that expects youth to have chastity, should facilitate conditions of obtaining chastity” (Nandi, 2015). He further added that people corrupted in atmosphere of previous Regime can be rehabilitated. “If Mut’ah was not banned, and people in need were allowed to have temporary marriages, no one would be infected with adultery (Edmore D. , 2015).

What was once considered a social taboo has gained momentum and vectored into acceptance. During the past few years, the ninth government, Ahmadinejad’s first administration, 2005-9, and the seventh and eighth parliaments have turned the revival of this custom and its promotion as “temporary marriage” into one of the foundations of their sexual politics.

The government and the parliament went so far as to ratify the new family law bill despite women’s strong opposition. This bill gives legal justification to conditional polygamy, including multiple [permanent] wives and Sigheh. It no longer even requires permission from the first wife. (Sadeghi, 2010)

In 2014, there was a publication of an official 82-page report that literally exposed the covert world of sex and detailing Iran’s rampant prostitution. Sex of every kind was taking place outside the marital bed in the Islamic Republic.

The report revealed secondary-school pupils and young adults were sexually active, with 80% of unmarried females having boyfriends. Illicit unions are not just between girls and boys; 17% of the 142,000 students who were surveyed said that they were homosexual.

As previously discussed the scope and pace of change, are challenging the government Iranian parliamentarians suggested Mut’ah marriage as a viable solution to the problem. This would allow to publicly register their union through the institution of Mut’ah marriage. (Economist 2014)

Temporary Marriage before the Islamic Revolution

Before the Family Protection Law approved in Iran in 1967, men were allowed to have four permanent and an unlimited number of temporary wives. But, according to the Law, men had to ask for the court’s permission to get married again (Ferdows, 1983).

The court was also responsible for studying about the man’s status and his financial capability, and call his first wife at a suitable time and questioning her in this regard. Therefore, remarriage without the court permission was regarded as a crime (Abbasi-Shavazi, Mohammad Jalal, and Peter McDonald. , 2012).

The family protection law approved in 1976 set more strict limitations on polygamy, maintaining the previous conditions. Based on the law, “consent of the first wife” was a mandatory condition for remarriage. The law contained exceptions; for instance, consent of a woman who was infertile or could not make sex with her husband was not required.

However, the woman had the right to ask for a divorce because of her husband’s remarriage. Nothing was mentioned about Sigheh in this law. But Iran Ministry of Justice had mandated official marriage registry offices to ask for a commitment from men requiring to get married again, indicating that they have no other wife (Higgins, 1985; Sanasarian, 2005) Topic of temporary marriage, which has been common for a long time, has been taken into consideration as a legitimate custom especially in religious cities.

Before 1956, women eager to have temporary marriage approached the local trustees, and they matched the people together (Higgins, 1985) (Sedghi, 2007). After 1956, issuing Sigheh contracts was halted under supervision of Farah Pahlavi; however, the marriage was practiced illegally and illegitimately (Blanch, 1978; Pahlavi, 1978).

In other words, after the ban on polygamy and prohibition of writing the term of discontinuous marriage in marriage contracts by Farah Pahlavi, this type of marriage was banned officially (the words permanent or discontinuous can be written in marriage contracts of now and then) (Blanch, 1978).

Quantitative Graphs of Temporary Marriage Study

The ground theory qualitative method was used for the purpose of analysing deep experiences of people who had practiced temporary marriage and Sigheh Mahramiat in Tehran, Mashhad, and Isfahan.

In this method, the focus was on producing theory, model or a conceptual framework, particularly, when there is no enough information on the topic of study. This approach is a type of public psychology for developing a theory based on the gathered data and their interpretation, which is constructed through the research process.

As no model has been presented so far for explanation and clarification of Sigheh Mahramiat/ temporary marriage, we used ground theory approach. The sampling method was meaningful and theoretical sampling guided continuation of the research afterwards for finding the theory. The study went on in a way that we reached theoretical saturation after conducting 100 interviews.

More interviews were done to make the results more reliable and after 216 interviews, the comprehensiveness of the study and the theoretical saturation seemed convincing. We enjoyed the supervision and guidance of qualitative method experts all through the way. 35% of the 216 participants were men and 65% were women.

Moreover, 82.7% of these people had a diploma or were in lower educational level. In addition to interview with people who had experienced Sigheh Mahramiat/temporary marriage, interviews were made with religious experts and scholars, legal experts, attorneys, and the marriage registry officers as well.

Findings of the Study:

After interpreting the interviews conducted in the field of study with the people having the experience of temporary marriage/Sigheh Mahramiat, various reasons of practicing the marriage were found.

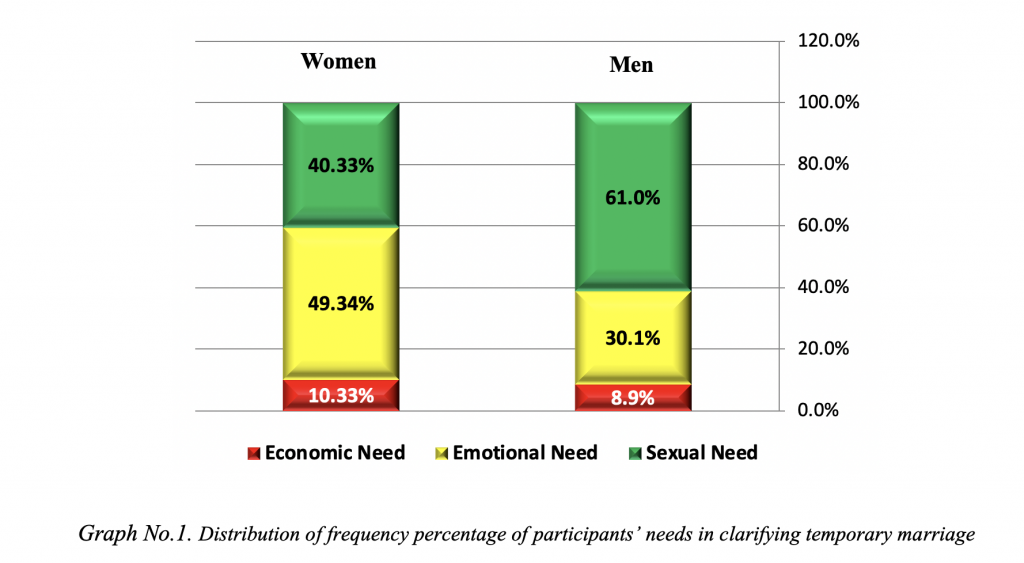

A topic seen in majority of the interviews was the matter of needs. Sexual, emotional, psychological and economic needs are the reasons of practicing temporary marriage. Based on achievements of this study, the main reason of practicing temporary marriage by men is the sexual needs.

Sexual needs being 61%, emotional needs being 31.1% and economic needs with 8.9%, are the first to third priorities of needs in statistical population of men. But the main reason encouraging women to practice temporary marriage is the emotional needs with 49.34%. Sexual and financial needs are the second and third factors with the percentage of 10.33% and 40.33%.

According to the data of this study emotional needs in women and sexual needs in men are the main reasons of practicing temporary marriage. Also, the experience of feeling loneliness and not being happy among women and the experience of unsuccessful marriage in the past, dissatisfaction of the pairs and lack of mutual understanding among men are recognized as the main reasons of practicing the marriage.

Based on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs physiological needs (first level of needs) and love/belonging needs (third level) are among the primary needs of human being. The human will not reach self-actualization and elevation unless his basic needs are met. Men, whose sexual needs are not met in the framework of family, tend to practice temporary marriage.

Reasons like variety seeking of men, lack of interest in the spouse, or illness and sexual problems of the spouse, and family problems and arguments lead men towards meeting their needs outside the house.

Temporary marriage paves the way for men easily because of availability, religious legitimacy, and lack of legal responsibility.

On the other hand, widows and divorced women prefer temporary marriage to permanent one due to loneliness and emotional problems, economic needs and the fear of repeating previous bitter experiences, despite being aware of social indecency of temporary marriage. Based on hector’s rational choice theory and Homan’s social exchange theory, it is concluded that men and women submit to temporary marriage due to the privileges they receive.

Thus, they consider temporary marriage more rational and cost-effective than permanent one.

Temporary Marriage-The Approved Way of Submission

The promotion of temporary marriage, has pushed pressing gender issues to the background as the masculinity benefits dominates the topic. The marriage in reality is a power imbalance predominantly in favour of men.

It gives men the right to have multiple sexual partners whilst stigmatizing women who do the same. The first beneficiary recipients of temporary marriage for majority are sexually men, often frustrated and or bored.

It has been also put forth that a woman suffers the same consequences from a permanent marriage as she does from her husband’s temporary marriage.

When a woman who is married permanently to a man who has entered into a temporary marriage, this imposes a new and deep-rooted form of inferiority on women. One seriously questions whether or not there any Muslim women who are happy with their husbands sharing their bed with other women under the guise of temporary marriage.

(Ghaderi 2014) In essence no woman can be sure that her husband is not in a sexual relationship with another woman. (Hawramy 2010).

It has also been put forward that that temporary marriage are favourable for men in its lopsided unbalanced bargaining position. Temporary marriages give the men a robust tool to prevent the victims (the women) from suing them for rape. The man can argue that the sex was conducted legally according to the Islamic law.

Clerics themselves have long been suspected of being amongst its biggest beneficiaries, sometimes when they are on extended holy retreats in ancient religious cities such as Qom (Economist 2014). Religious traditions indicate that there is no limitation for men in number of temporary marriages and they do not need to undergo Iddah, the period after her husband’s demise, in which the woman has been instructed to refrain from getting married again. (Hashmi 2018).

In addition, in sigheh, the man not only thinks that his action is halal according to Islam and God, but also he feels positively about his treatment of the woman because God is going to reward him. In Shia Islam, it is said that those men who participate in temporary marriages get a special blessing from Allah (God) because they are doing a favor to the women.

Furthermore, these kinds of temporary marriages give the men a robust tool to prevent the victims (the women) from suing them for rape. The man can argue that the sex was conducted legally according to the Islamic law.

Although it is referred to as “marriage,” sigheh provides the perfect environment for the man to easily dodge responsibility and relieves the man from any kind of commitment.

In reality, he treats the women as a sex tool. And normally, no one will permanently marry a woman who was once in sigheh even if she was forced into it. The word “marriage” here belies the fact that sigheh is solely “a pay for sex” contract.

Ironically, this Islamic law, which was aimed at helping the Shia Islamic Imams exploit women, is now being used against them as a method of resistance. Many young Iranians who want to escape punishment for being together argue that they are in sigheh when they get arrested by the moral and religious police.

Sigheh, the temporary marriage, is another Islamic method in Iran to exploit, subjugate and dehumanize women. Iran’s Imams and clerics have their “Islamic” way to sleep with women for as long as they desire and to force women into sex.

While Iranian mullahs and officials criticize premarital sex in the West and they bash the Western concept of having a boyfriend or girlfriend, they are totally fine with their actions of “religiously” and “legally” paying women for sex or forcing them into sigheh.

The study reveals that the marriage is not accepted in the Iranian’s common law as it depends on sexual needs; the marriage is regarded as the reason of corruption and variety seeking.

Based on Bauman and Giddens theories of liquid love, relationships are short-lived in a modern society, connected to individual transitory pleasures (Bauman, 2013). The features of the short-lived modern relations are obviously seen in temporary marriage too.

These features are not accepted by the public and romantic relations in the old times are preferred in different sections. In addition, temporary marriage reproduces social inequalities and sexual discriminations.

Women have fewer job opportunities due to the sexual discrimination in Iran’s market, thus they sometimes have to submit to temporary marriage in order to meet their economic needs. These matters have created a market in Iran for middlemen and cyber social networks and also some Arabs and men of neighbouring countries. The market improves a type of pleasure economy and sexual tourism.

These actions are not hidden from the public eye and there has always been a negative attitude towards Mut’ah women based on the common law. On the other hand, women are to be blamed for part of the inequality they face in temporary marriage.

They decorate themselves for men, and managing their body, women expose themselves to men that abuse them sexually. Heavy payments are exchanged among middlemen and those seeking such women. However, women do not take much advantage of this exchange, and physical, spiritual losses are what they finally receive.

Igniting Gender based violence

Temporary marriages exploit, subjugate and dehumanize women. Mut’ah is for the benefit of men in all cases, particularly in current conditions. Mut’ah “marriages” are only hiding behind the thinnest façade of legality and posing as a sacred element of a world religion for only one reason: to maintain men’s domination over women.

Given that temporary marriage provides the conditions for men so that they can satisfy their desire for sexual diversity; or they can meet their needs when they are hypersexual and their spouse cannot be responsive (Haeri, 2014). The one-sided advantage men take from temporary marriage becomes more obvious when married men go through it;

as such marriages are not registered and will not be punished either, being supported by religion. Although religious and governmental policymakers in Iran are making attempts to implement reforms over temporary marriage, no measure has been practically taken in this regard. Social and human rights activists, particularly females criticize such marriages, calling them illegal, irreligious, and inhumane (Afshari, 2011).

To them temporary marriages are simply wives for an hour. (Rafizadeh 2016) reinforcing the idea that for woman the only path to emancipation is through the Harem. (Sadeghi 2010).

Analysing strategic action and interactions in temporary marriage, such relations were defined as being transitory. Moreover, interpreting the interviews revealed that interactions in temporary marriage are limited and short-lived, with specified ending.

These interactions have negative effects on both parties, especially on women. Furthermore, emotional, economic, and sexual interactions were analysed in this type of marriage, showing a kind of inequality for the benefit of men.

Two factors were analysed in the section of pivoted topic, containing the most important mutual understanding among all the researchers and interview interpreters. These two factors which are obvious in the whole structure of the research are pleasure seeking and child marriage.

Temporary marriage is based on pleasure seeking originally and the word Mut’ah has the same meaning as well. However, the evidence and the interviews showed that men are the ones who enjoy more.

There were some cases in this study in which the women had to pay for some economic needs of their partners in addition to satisfying them sexually; so that they could take reciprocal sexual advantage.

This type of pleasure-seeking is a kind of perilous lifestyle derived from individuality and autonomy of modern lifestyle. Based on sexual needs, the younger the woman is, the more is the joy and the sexual pleasure in a relation.

Therefore, this type of pleasure-seeking promotes sexual deviations like paedophilia, which pave the way for those with sexual deviations or mental disorders to abuse young girls sexually.

In case these people cannot practice temporary marriage legally, they will satisfy their desire through raping the innocent kids. Also, not specifying an exact age for temporary marriage and ambiguity of the subject, and also not paying attention to the age of Sigheh Mahramiat in the law facilitates child marriage.

Several undesirable consequences were identified based on the interviews and the related interpretations, in the section of consequences. It is worth mentioning that temporary marriage had a positive function only in one interview.

The most important consequences of temporary marriage achieved in interviews conducted in the field of study include:

pleasure economy, corruption and prostitution in society, negative attitude towards permanent marriage, promotion of scepticism, shaking family foundation and rise of divorce, child marriage, child widowhood, quitting education, violating women’s rights and discrimination against them in economic, legal and emotional dimensions. Economy of pleasure is rooted in heavy payments exchanged by middlemen, Arabs and some pleasure seeking wealthy people, in sexual tourism through practicing Mut’ah.

Moreover, as there is no supervision and because of women’s infidelity, undergoing Iddah period is disregarded and such relationships are a type of whoring for earning money as a result, leading to rise of prostitution in society. Also, the interviews indicated that a kind of scepticism and reluctance towards permanent marriage is created in people as they practice transitory relations with unfaithful characters over and over again. The modern nuclear family which is formed based on love, will not tolerate betrayal of the pairs and these types of marriages lead to family collapse.

On the other hand, temporary marriage practiced in the framework of Sigheh Mahramiat facilitates child marriage.

At these ages, teenager’s parents make their children marry someone under their supervision, but they may start having sex after a while and become pregnant unintentionally.

Besides, the data indicated that children will quit education in case their families insist on early marriage. On the other hand, if the man does not undertake the responsibility of the child born of the marriage, numerous financial, social and spiritual problems will be imposed on the wife and her family leading to consequences like child widowhood.

Discrimination against women was among other consequences of temporary marriage. There are countless limitations for women over the different legal dimensions of the marriage including legacy, Nafaqa, marriage registration and economic issues.

In addition, as women are afraid of being discarded and stigmatized, they withdraw from filing lawsuits against their violated rights in temporary marriage.

Moreover, the punishments specified for violence against women in temporary marriage are not clear and the legislator has kept silent in many cases. Based on the study achievements in the field of study, a model is presented below in which temporary marriage is a dependent variable. The factors affecting the marriage are also considered as independent variables. Here is the model for effects and consequences of temporary marriage:

Discussion- Why Women submit to temporary marriage

There are needs hidden in women, which can be met through permanent, steady marriage and continuous loyalty. Mut’ah wives however, start a temporary union with an ideal image from permanent marriage, while their needs and desires are suppressed.

But short after temporary marriage, their suppressed desires are awakened, and this may be why they face depression and psychological failures after termination of the marriage (Bartkowski, John P., and Jen’nan Ghazal Read, 2003).

Some needs are inseparable from the woman’s essence, but they are difficult to be satisfied in temporary marriage because of the emotional identity of woman and as the marriage has sexual foundation. The need to love and emotional relations, the need to social acceptance, the need to have children and economic needs are among the said requirements (Rafei, 2003).

One of the most important women’s needs is the desire to be loved and appreciated by another person. But she will experience insecurity, mental contradictions and emotional divorce when she is treated in a commercial manner.

For women, marriage is beyond passion and sexual desire and according to Quran, marriage creates love and friendship between partners (Haeri S. , 1990). Women are in search of steadiness in love, strong loyalty, continuous affection and a permanent husband. Sexual joy may end one day, but there is no ending for women’s love and emotional needs. Therefore, mental, spiritual and social disorders will be caused for women after termination of temporary marriage.

The social aspect of marriage is of significant importance for women (Cutrona, 1996). Specifically, in Iranian culture, women consider marriage as a stabilizing factor. In many communities and cultures, particularly in traditional communities, the woman is identified with her husband’s last name after marriage.

If the husband has a suitable social economic status, the woman’s social acceptance is increased and she will be respected more than before among family and friends. In many cases, none of the woman’s needs are met as the temporary marriage is not disclosed; as a result, the woman faces a great amount of suppressed desires (Shahrikandi, 1989).

Many people believe that, becoming a mother is the greatest the most beautiful and the most artistic event of a woman’s life. The woman wants to have a child of her own nature so that she can teach her/him of the love, affection and morality she owns. It is possible to have a child in temporary marriage, but it is not recommended owing to the bitter consequences.

In addition to the problems of accepting ownership of the child by the man, the legal problems for registering the child’s ID triggers social mental consequences for the child too. Preventing pregnancy is usually one of the hidden pillars and the implicit conditions of temporary marriage. In case of pregnancy, abortion is normally done through various illegal and unhygienic methods (Aníbal Faúndes, José Barzelatto, 2006).

Economic concerns are a major part of women’s life, making them worried about the future. Thus, some of them try to protect their economic security by purchasing valuable goods like jewelries.

In traditional societies, men have always been the women’s caretakers; father, brother, husband and grandfather supported women financially. But the female household caretaker has to pay for the subsistence of herself and her family (children, father, old mother).

Some women caretakers who do not have enough work and skills usually find the best way out of this situation as temporary marriage. The religious reason of temporary marriage for men is deemed to be poverty and temporary marriage practiced by rich men is often criticized.

This is while, the experiences and the field studies indicate that rich men are more willing to have temporary marriage and also Mut’ah women are eager to marry wealthy men as well.

Many of these Mut’ah women marry wealthy men and are suddenly left alone after experiencing a period of economic welfare, when the man is saturated in the relationship. This is while women economic expectations have increased after marriage and the separation can lead to constancy of poverty cycle and increase women’s economic needs (Swain, 2013).

Conclusion Temporary Marriage

Mut’ah is not a topic with positive functions. Rather, it causes harms like child marriage, collapse of family foundation, negative attitude towards permanent marriage, promotion of corruption and violation of women’s rights.

Temporary marriage and Sigheh Mahramiat is a social phenomenon operating within in Iran’s legal and religious culture. Lack of other needs such as security in society, emotional, sexual and cultural needs affect opinions of women towards temporary marriage (Zahed, Seyyed Saeed. Kheiri, Behnaz, 2001. However the pleasure is short lived.

Emotional and psychological issues generated in short term and medium term relationships endanger women’s mental health (Qazvini, 2014). Given that after the end of Sigheh, the marriage is annulled automatically and once again women face the responsibilities, and economic psychological pressures. Furthermore, women may become used to such relationships forming attachments that may not be reciprocate.

This may result in ensuing angst, emotional and separation anxiety when the temporary marriage abruptly comes to an end. Critics have reasoned that temporary marriages allow for the exploitation of women, with men taking on multiple “wives” for a number of hours. (Mahmood and Nye 2013). This ignorance goes squarely against the debate of social justice and rising chorus of acknowledgement of gender equality in modern nuclear family (Shay, 2014).

The analysis of the whole Temporary Marriage scenario indicates that society invariably picks culture over law. The laws that seem to be in line with the cultural beliefs are the ones that are followed.

On the other hand, laws that are not aligned with the cultural practices of the society must be molded to conform or are ignored. The characteristics of mutta correspond with traditional Shi’a Iranian views towards women. The institution is a design which helps satisfy men’s sexual desires but fails to recognize the women’s needs and desires.

The institution fundamentally disadvantages women, a characteristic which is consistent with Islam’s traditional treatment of women in Iran.

Since constraints on girls’ capabilities are often the result of gendered rules dictated by fathers and husbands, it is vital that men and boys are engaged in conversations about changing normative gender beliefs and practices.

Helping men to learn about new forms and practices of masculinity through awareness-raising and education initiatives – led by professionals who have experience in working sensitively with boys and men – is crucial to bringing about change.

Efforts should involve collaborations with organisations that promote caring, non-violent and equitable masculinities and gender relations internationally, by taking to scale effective approaches that reach out to men and boys to reduce violence against women.

About the Author Temporary Marriage

Kameel Ahmady is a Social Anthropologist and scholar who is the recipient of the 2017 Truth Honour Award by the London Law University and the IKWR Women’s Rights Organisation. He also is the recipient of 2018 first place winner award of Literary Category by Global P.E.A.C.E. Foundation at the George Washington University in D.C. Kameel has worked mainly on international and social development on gender and minority related issues. His previous pioneering research books have garnered International attention and are published in English, Farsi, Turkish and Kurdish languages. “Another look at east and south east of Turkey” (Truism with the touch of Anthropology) published by Etkim, Istanbul-Turkey 2009 and research of “In the Name of Tradition” (A Country Size Comprehensive Study on Female Genital Mutilation FGM/C in Iran), published by Uncut Voices Press-Oxford- 2015 also “An Echo of Silence” (A Comprehensive Study on Early Child Marriage ECM in Iran) published by Nova Science Publisher, Inc., New York 2017. “A House on Water” (A Comprehensive Study on temporary Marriage in Iran) and “Childhood plunder” ( A research study on child scavenging –Waste picking- in Tehran/Iran printed and lunched in 2019 in Iran/Tehran. His new books “Forbidden Tale” (A Comprehensive Study on Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual (LGB) in Iran (2018) and “A House under shadow” (A Comprehensive Study on temporary Marriage in Iran) are printed in English and Farsi by Mehri publishing in 2020.

References Temporary Marriage

Abbasi-Shavazi, Mohammad Jalal, and Peter McDonald. (2012). Family change in Iran: Religion, revolution, and the state.” International family change. 191-212.

Abbasi-Shavazi, Mohammad Jalal, and Peter McDonald. . (2012). “Family change in Iran: Religion, revolution, and the state.” International family change. Routledge, 191-212.

Aníbal Faúndes, José Barzelatto. (2006). The Human Drama of Abortion: A Global Search for Consensus. Vanderbilt University Press.

Bartkowski, John P., and Jen’nan Ghazal Read. (2003). Veiled submission: Gender, power, and identity among evangelical and Muslim women in the United States. Qualitative sociology 26.1, 71-92.

Bauman, Z. (2013). Liquid love: On the frailty of human bonds. John Wiley & Sons.

Bayat, A. (2013). Life as politics: How ordinary people change the Middle East. Stanford University Press.

Blanch, L. .. (1978). Farah, Shahbanou of Iran, Queen of Persia. HarperCollins.

Cutrona, C. E. (1996). Social support in couples: Marriage as a resource in times of stress. Sage Publication.

Dabashi, H. (2017). Theology of discontent: The ideological foundation of the Islamic revolution in Iran. Routledge.

Edmore, D. (2015). Reflections on Islamic marriage as panacea to the problems of HIV and AIDS. Journal of African Studies and Development, 183.

Ferdows, A. K. (1983). “Women and the Islamic revolution.”. International Journal of Middle East Studies 15.2 , 283-298.

Haeri, S. (1990). Law of Desire: Temporary Marriage in Iran. London.

Haeri, S. (2014). Law of desire: Temporary marriage in Shi’i Iran. Syracuse University Press.

Hashemi, B. E. (2013). Temperance and Victory (Hashemi Rafsanjani Records and Memories. Tehran: Publication Office Revolution Learning.

Higgins, P. J. (1985). Women in the Islamic Republic of Iran: Legal, social, and ideological changes. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 10.3, 477-494.

Jakesch, M. a.-C. (2012). The mere exposure effect in the domain of haptics.

Johnson, S. A. (2013). Using REBT in Jewish, Christian, and Muslim couples counseling in the United States. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy 31.2 , 84-92.

Kalantari, A. A. (2014). Qulitative Study of Conditions and Backgrounds of Women’s Temporary Marriag. Woman in Policy and Development.

Manzar, S. (2008). Muslim Law in India. Orient Publishing Company, 2008, p-125.

Murata, S. (2014). Muta’, Temporary Marriage Islamic Law. Lulu Press.

Najmabadi, A. (2013). Professing selves: Transsexuality and same-sex desire in contemporary Iran. Duke University Press.

Nandi, A. (2015). Women in Iran.

Pahlavi, F. (1978). My thousand and one days: an autobiography.

Pahlavi, F. (1978). My thousand and one days: an autobiography.

Parishi, M. (2009). Analyzing Temporary Marriage Backgrounds and Consequences for Women. Allameh Tabataba’i University. MA Thesis.

Philip Setel, Milton James Lewis, Maryinez Lyons. (1999). Histories of Sexually Transmitted Diseases and HIV/AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa. Greenwood Publishing Group.

Rafei, T. (2003). Analysis of woman psychology in temporary marriage. Tehran: Danjeh.

Riahi, M. E. (2011). Identifying Social Correlations of Level and Reasons of Agreement or Disagreement with Temporary Marriage. Family Research Quarterly, 8(32), 485-504.

Rizvi, S. M. (2014). Marriage and Morals Islam. Lulu Press.

Sanasarian. (2005). Women’s Rights Movements in Iran: Mutiny, Appeasement and Repression from 1900 to Khomeini, Translated by Nooshin Ahmadi Khorasani. Tehran: Akhtaran.

Sedghi, H. (2007). Women and Politics in Iran-Veiling, Unveiling, and Reveiling. Newyork: Cambridge University Press.

Shahrikandi, A. (1989). Personal Status and rights of Partners, collected by Mohammad Samadi and Abolaziz Tayeed. .

Strauss, Anselm and Corbin Juliet. (2011). Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, Translated by Biyuk Mohammadi. Tehran: Research Center of Human Sciences and Cultural Studies.

Swain, S. (2013). Economy, Family, and Society from Rome to Islam: A Critical Edition, English Translation, and Study of Bryson’s Management of the Estate. Cambridge University Press.

Tiliouine, Habib, Robert A. Cummins, and Melanie Davern. (2009). Islamic religiosity, subjective well-being, and health. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 12.1, 55-74.

Temporary Marriage

Farsi (فارسی)

Farsi (فارسی) Kurdish (کوردی)

Kurdish (کوردی)